Most access control problems don’t show up on day one. Doors unlock. Badges scan. Everything looks fine. The gaps only become visible later when a door is forced open, and no alert triggers, when access logs don’t explain who entered, or when a simple upgrade turns into a costly re-wiring project.

In almost every case, the issue isn’t the brand of system used, but a poor understanding of how its core components are supposed to work together.

This guide breaks down the five essential components of an access control system in practical terms. You’ll see what each part does, how they interact during real entry and exit scenarios, and where teams often cut corners that later create security or compliance risks.

By the end, you’ll have a clear framework for evaluating, designing, or upgrading an access control setup without needing to wade through technical jargon or vendor marketing.

- The five core components every modern access control system relies on

- How access is granted, denied, and logged across doors and users

- What to consider when choosing or upgrading an access control system

5 Components of an Access Control System

Every access control system, regardless of size or vendor, is built around the same core components. These parts work together to decide who can enter, when they can enter, and what happens if access is denied or misused.

If even one component is missing, misconfigured, or poorly integrated, the system may still “work” on the surface, but it won’t deliver real security or visibility.

Below are the five essential components you’ll find in a modern physical access control system, followed by a detailed explanation of how each one works.

1. Access Control Credentials

Credentials are what users present to prove their identity. They act as the system’s starting point without a credential; no access decision can be made.

Common credential types include access cards, key fobs, PIN codes, mobile credentials, and biometric identifiers like fingerprints or facial recognition. Each credential is uniquely tied to a user profile inside the system, allowing administrators to grant, modify, or revoke access without changing physical locks.

Stronger systems support multi-factor authentication, combining two credential types (for example, a card plus a PIN) to reduce the risk of unauthorized access.

2. Card Reader / Access Reader

The reader is the device installed at the door that captures credential data. Its role is simple but critical: read the credentials and pass that information to the controller for verification.

Readers vary based on credential type, such as RFID card readers, keypad readers, mobile readers, or biometric scanner,s but they all serve the same function. Modern readers may also support encrypted communication and two-way messaging with the controller, improving security and reliability.

The reader itself does not decide whether access is granted. It only collects and forwards data.

3. Access Control Panel (Controller)

The controller is the decision-maker of the system. It receives credential data from the reader, checks it against access rules, and determines whether the door should unlock.

Controllers store access permissions, schedules, and rules locally or sync them from centralized software. Once a credential is verified, the controller sends a signal to the door hardware to unlock for a defined time and logs the event for auditing.

In larger systems, a single controller may manage multiple doors, while smaller setups may use one controller per door.

4. Door Hardware (Locks & Sensors)

Door hardware is the physical layer that secures the entry point. This includes electronic locks and supporting sensors that provide context around door activity.

Locks can be electromagnetic locks, electric strikes, electrified handles, or crash bars, depending on the door type and safety requirements. Sensors like door position indicators (DPIs) and request-to-exit (REX) devices help the system understand whether a door was opened normally, forced open, or left ajar.

Without these sensors, the system may grant access but fail to detect misuse or security incidents.

5. Access Control Software

Access control software ties everything together. It’s where administrators manage users, assign credentials, configure access rules, and review activity logs.

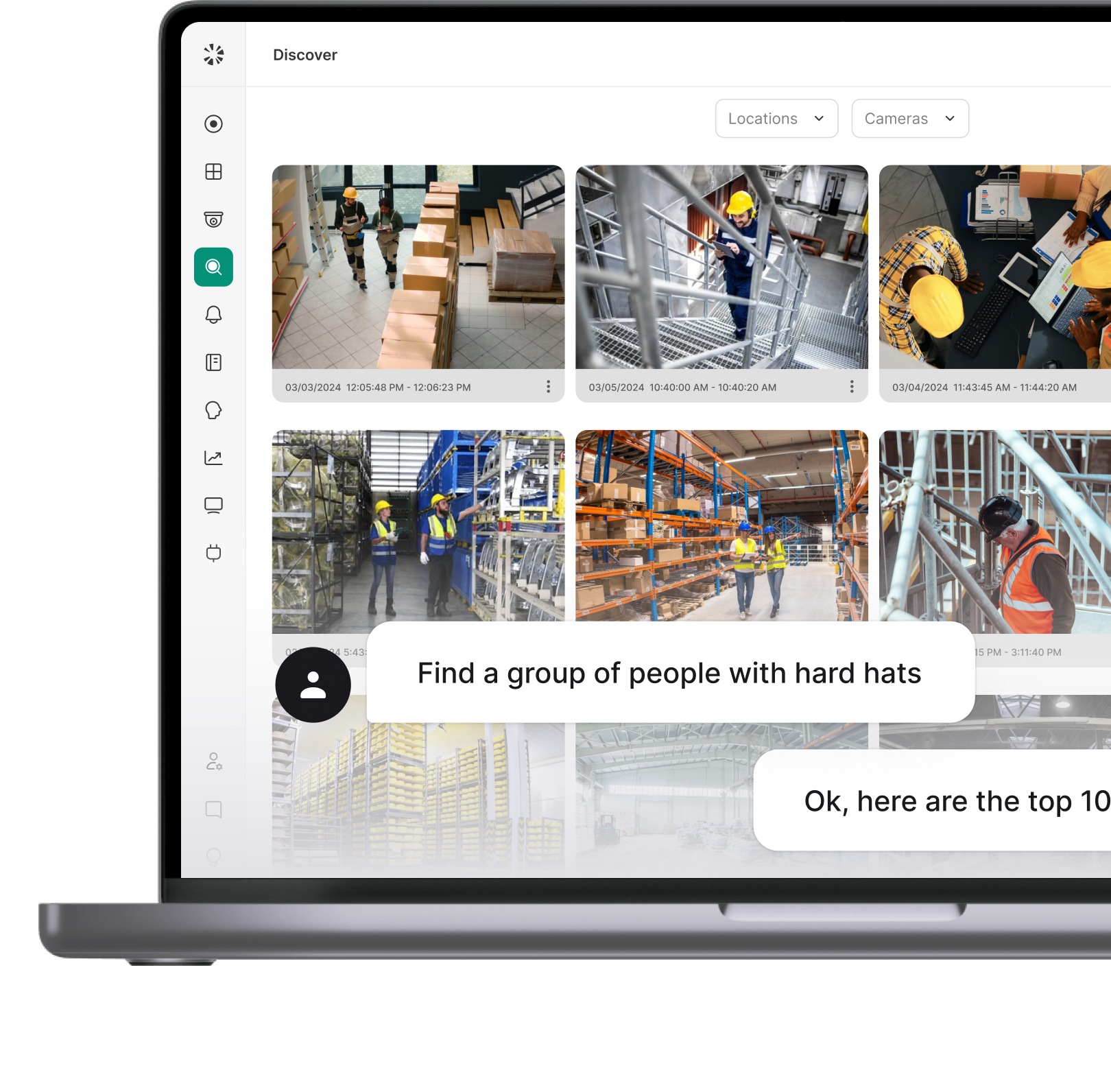

Modern systems often use cloud-based software, allowing remote management, real-time alerts, and easier scaling across multiple locations. The software also enables reporting, audits, and integrations with other systems like video surveillance, alarms, or visitor management tools.

In short, the software turns raw door activity into actionable visibility.

How Access Control Systems Work (All Components Together)

An access control system only works when credentials, readers, controllers, door hardware, and software operate as a single chain. Each component depends on the others, and no part can function in isolation.

Here’s how all five components interact during a real access attempt:

1. Credentials initiate the request: A user presents a credential such as a card, PIN, mobile pass, or biometric. This is the identity input that starts the access process.

2. The reader captures and forwards the data: The access reader scans the credential and sends the data to the access control panel. The reader does not grant access; it simply passes information upstream.

3. The controller evaluates access rules: The access control panel checks the credentials against permissions, schedules, and door-specific rules stored locally or synced from the access control software. At this point, the system decides whether access should be allowed or denied.

4. Door hardware executes the decision: If access is approved, the controller signals the electronic lock to unlock for a defined time. Door sensors such as door position indicators (DPIs) and request-to-exit (REX) devices confirm whether the door was opened normally, forced open, or left ajar.

5. Access control software records and monitors activity: The software logs every event, successful or not. It provides visibility into who accessed which door, when, and under what conditions, and can trigger alerts if something deviates from normal behavior.

All of this happens in under a second. But if any component is missing, no sensors, weak credentials, or poorly configured software. The system may still unlock doors while failing to detect misuse, policy violations, or security incidents.

What Happens When Access is Denied?

When access is denied, the system is doing more than just refusing entry. It’s validating rules, protecting the door, and deciding whether the situation is routine or something that needs attention.

At the door, the most visible outcome is simple: the lock never disengages. There’s no temporary unlock, no door movement, and in many cases, no obvious feedback to the user beyond a reader beep or indicator light.

Inside the system, however, more is happening. The controller records the failed attempt and sends the event to the access control software, where it becomes part of the audit trail. These records show who tried to enter, which door they approached, and when the attempt occurred. Over time, this data helps teams spot patterns such as repeated access attempts outside approved hours or credentials being used after they were revoked.

In higher-risk scenarios, denied access can trigger additional responses. Systems may raise alerts after multiple failed attempts, flag unusual behavior, or link the event to nearby cameras for visual verification. If door sensors are present, the system can also confirm whether the door stayed closed after access was denied or whether it was forced open.

Not every denied attempt signals a threat. Many are caused by expired credentials, schedule restrictions, or role changes. What matters is that the system captures the context. Without logging, alerts, and sensor feedback, denied access becomes just a locked door with no insight into whether it was harmless or a warning sign.

How to Choose the Right Access Control System?

Choosing an access control system isn’t about picking the most advanced technology on paper. It’s about matching security requirements, building layout, user behavior, and long-term operations into a system that stays reliable years after installation.

A good decision upfront prevents expensive rework, compliance gaps, and daily operational friction later.

1. Assess Your Security and Operational Needs

Start by understanding what you’re trying to protect and how people move through the space.

Identify which areas actually need access control. Not every door requires the same level of security. Server rooms, medication storage, data centers, and restricted offices demand tighter controls than common areas or internal corridors.

Next, look at the user flow. High-traffic entry points may need faster authentication methods to avoid bottlenecks, while low-traffic or sensitive areas can justify stricter verification.

Also factor in compliance and safety requirements. Fire codes, emergency egress rules, and industry regulations often dictate how locks, sensors, and fail-safe behavior must be configured.

2. Choose the Right Credential and Reader Technology

Credential choice affects both security and daily usability.

Card and key fob systems are simple and familiar, making them suitable for many environments. Mobile credentials reduce physical badge management but depend on device compatibility and user adoption. Biometric authentication offers higher assurance but requires careful placement and privacy consideration.

In higher-risk areas, combining credentials such as a card plus a PIN or biometric adds protection without redesigning the entire system.

The goal is to align authentication strength with real-world risk, not apply the same method everywhere.

3. Evaluate System Architecture and Core Features

The underlying system design determines how flexible and future-proof the solution will be.

Consider whether the system supports:

- Scaling to additional doors or sites

- Centralized vs distributed control

- Integration with video surveillance, alarms, or visitor systems

- Remote management and monitoring

- Offline operation during network outages

A system that works well for a single building today should not limit expansion tomorrow.

4. Look Beyond Upfront Cost

Initial pricing only tells part of the story.

Total cost of ownership includes installation complexity, cabling requirements, ongoing maintenance, credential replacement, software licensing, and support. Systems that appear cheaper upfront can become expensive to operate if updates, changes, or troubleshooting require constant vendor involvement.

Reliability, vendor support quality, and long-term maintenance effort matter just as much as purchase price.

5. Plan for Deployment and Ongoing Use

Implementation affects whether the system actually delivers value.

Involve security, IT, and facilities teams early to avoid design conflicts. Ensure administrators are trained to manage users, schedules, and alerts. For larger environments, a phased rollout reduces disruption and helps identify issues before full deployment.

An access control system isn’t a one-time install; it’s an operational system that must adapt as people, spaces, and policies change.

From Components to Confident Control

You’ve seen how access control works when every component is planned with intent. Credentials, readers, controllers, door hardware, and software each play a clear role in keeping access predictable, traceable, and manageable across real environments.

- Access control works best when every door action is logged and explained, not guessed

- Sensors and rules add context to access events, improving response and audits

- Thoughtful system design reduces operational friction and long-term rework

- Choosing the right architecture early supports growth without disruption

If you’re looking to put this into practice, Coram supports modern access control setups by bringing visibility, intelligence, and day-to-day manageability into one streamlined system.

Ready to apply this across your doors and locations? Book a demo or start a free trial to see how Coram brings access control together in one system.

FAQ

A physical access control system is built around five core components: credentials, readers, controllers, door hardware (locks and sensors), and access control software. Credentials identify the user, readers capture that identity, controllers make the access decision, door hardware enforces it, and software manages rules, logs, and visibility across the system.

The “5 Ds” describe how access control supports security operations across a facility:

- Deter unauthorized access through visible controls

- Detect access attempts and abnormal behavior

- Deny entry when credentials or rules don’t match

- Delay intrusion long enough for a response

- Document every access event for audits and investigations

Together, they ensure access control is proactive, not just reactive.

A user presents a credential to a reader. The reader sends the data to the controller, which checks access rules and schedules. If approved, the controller unlocks the door briefly; if denied, the door stays locked. Every attempt, successful or not, is logged by the software for monitoring and review.

Yes. Most systems can continue operating locally even if the internet goes down. Controllers store access rules on-site, allowing doors to function normally. Internet connectivity is mainly required for remote management, cloud dashboards, updates, and centralized reporting, not for basic door operation.

%20(56).webp)